Constance Furey, Ruth N. Halls Professor of Religious Studies at Indiana University Bloomington, was guest speaker at the DSR Lecture Series event in early February, presenting "Unmooring Utopia: Death and Desire in Early Modern Christian Fictions," discussing the reinterpretation of the relationship between death and desire in Thomas More’s Utopia, a 1516 work that gave its name to literary designs for ideal societies. Co-founder of the Center for Religion and the Human, she directs two of its initiatives: Teaching Religion in Public and the Being Human Institute for Emerging Scholars. Her latest book is the co-authored Devotion: Three Inquiries in Religion, Literature, and Political Imagination, published by University of Chicago Press. During her visit to the Department for the Study of Religion, Furey met with DSR MA student Emily Amos-Wood to talk about her scholarly work alongside its relationship with the public-facing projects with which she is involved. The interview has been shortened and edited for clarity.

What brought you to Thomas More's Utopia and its consideration, or lack thereof, of death and violence?

I'm always drawn to texts that seem enclosed by canonical interpretations, and whether surprising and unexpected things can be found. I first wrote on Emilia Lanier's poetry as a form of utopian writing, though it's not canonically considered a utopian work. Then I became interested in thinking about what is available in More's work that is occluded in certain ways by its thematic obviousness. I became interested in what Utopia conceals about the very extraordinary events that were happening at that time, specifically European exploration and its violence.

I want to ask you about faithful reading, and the hermeneutics of suspicion, which you, Amy Hollywood, and Sarah Hammerschlag discuss in the introduction to your book, Devotions. There’s an ongoing disciplinary conversation about how to read religious texts in a generative way given the context of colonialism and its impositions on other languages and traditions as acts of violence. But textualism is ultimately inescapable in our work, we have to engage with texts and reading practices. How do you conceptualize your reading practice in relation to these issues as a scholar of literature?

I think of faithful reading like riding in the wake. If you're drafting, in biking behind someone, then you aren't confronting quite so many headwinds. Faithful reading to me is something like that. There's a distance you never want to close, because you'd crash if you did, which is to say you'd fall prey to the destructive or alluring illusion that you can identify completely with what you read. This is the problem with trying to merge completely with something in a text that you either hate and want to destroy, or that you love and want to unite with. But there's something about letting it take you to a place that you wouldn't otherwise go that’s generative. Simultaneously, you recognize the need to keep some distance from it. That to me is a necessary balance -- the combination of critique and fidelity that I find important.

When I first started thinking about devotional reading, it was in response to the idea of surface reading, as an alternative to critique understood as a kind of judgment from on high or a sort of “aha!” move, where the critic has the power to reveal what regular readers can’t see. Surface reading tried to counter that kind of critique by saying readers should pay close attention to what the text explicitly says. I found both of those options really unsatisfying. It’s either depicting readers as extracting and telling you the “truth,” or proposing that we stay on the surface of the text and be completely subject to it. Both seem completely wrong. So I became interested in this long tradition in Christianity of discernment, which assumes that there is guidance available in the learning process, but that you can never be sure that what you're trying to learn is actually good or right. I think that a combination of innate confidence that something can be learned, with wariness about presuming you know exactly what you're learning, is the kind of suspension that, to me, is a faithful reading.

Frederick Jameson's a really important theorist for me. He has this famous line from his 1981 work called Political Unconscious, where he writes “always historicize.” In my generation, historicizing was what everybody aspired to do. However, I think they misunderstood in significant ways what he meant by that. You can never actually put anything in its historical context. You're always trying to cross that distance between your immediate context and the work to recognize the particularity of something, and then recognize how it traverses from that particularity to our apprehension of it, and its innate universality. That dialectical movement back and forth is how we find ways to write in fiction and scholarship, through invitations to avoid ready-made categories, condemnations, and explanations, while still looking at things that are easily occluded by dominant ideologies.

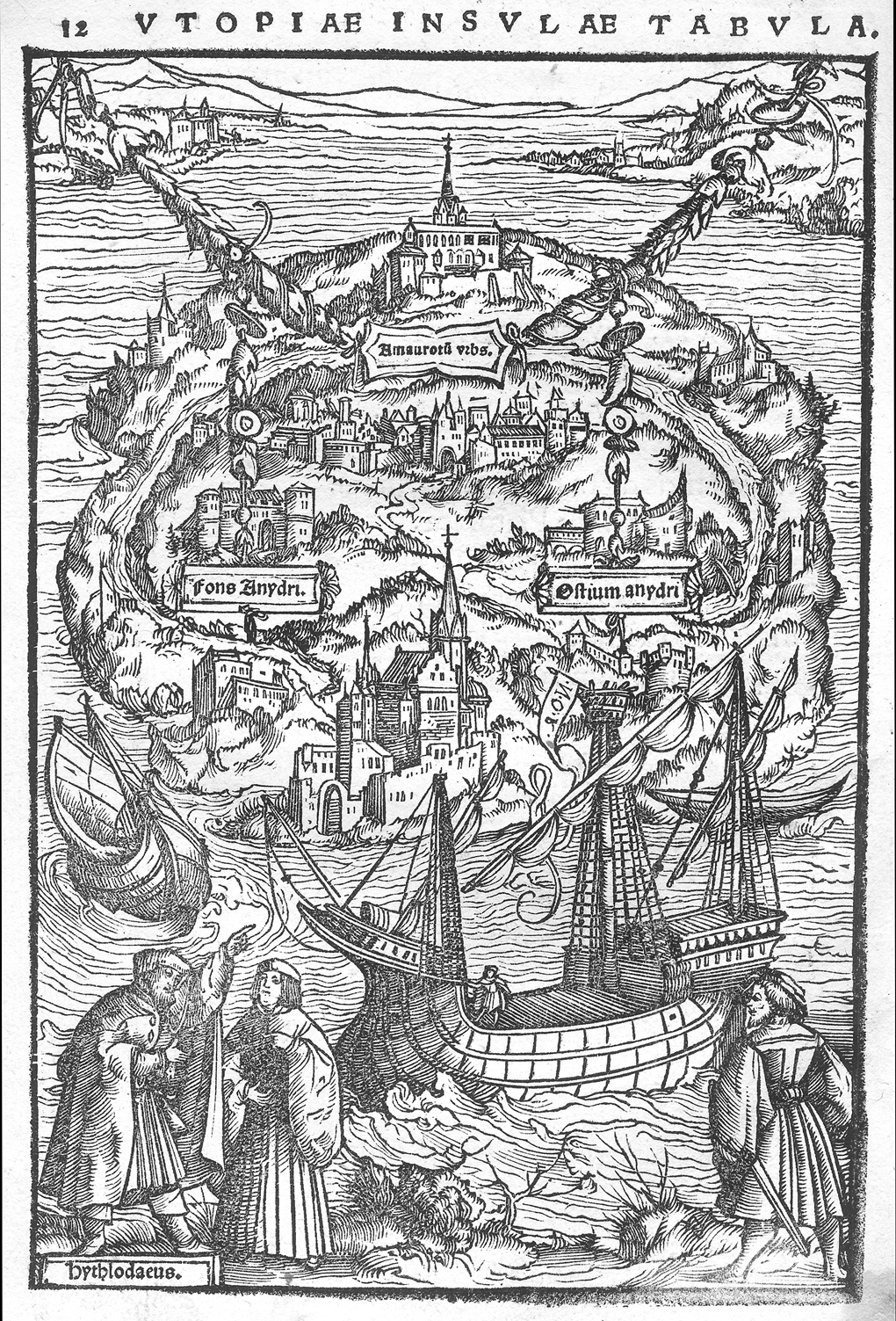

For example, the skull map in Utopia that I discuss in today’s talk is something you have to squint at to see. And there is a way in which I, for better and for worse, think that a lot of times what I'm trying to do in thinking through the horrors that are both implicit and, less frequently, explicit in the texts that I study is that sometimes the best way to approach them and see them in their full complexity is to squint a bit, to come at them awry.

Teaching religion is an exciting challenge because people have so many assumptions.

You're involved in other projects and initiatives that advocate for public scholarship in religious studies, through projects like the Being Human Institute for Emerging Scholars and Teaching Religion in Public. Why is that important work for you?

It's been crucial to see that public facing work is inseparable from the work of education. These projects have renewed my sense of the importance of recognizing the classroom as a public space. The limits and possibilities of what we can do in talking about religion can be explored in significant and exciting ways in classroom settings, particularly in public universities like Indiana and Toronto. In these contexts, if you're actually trying to engage with everyone in your classroom, and really hearing what they are and aren't understanding, and what they're bringing into the room, then you have the full complexity that is public engagement.

Teaching religion is an exciting challenge in a particularly acute way, because people have so many assumptions. They come into the classroom with hostility, fidelity, curiosity, wariness, but seldom indifference. Almost everybody has assumptions about Christianity. Many think, for example, that religious people want to do what God says, full stop. So then you introduce an idea like discernment, which is an interesting part of this tradition, often occupied by marginalized people like Teresa of Avila, who was certainly privileged in certain ways, and now a canonized saint but also subject to the Inquisition, and harassed, censored, and even imprisoned during her life. Teresa had to figure out if she was rightly understanding what God wanted of her, or whether church authorities were right when they told her she was deceived by the devil. Discernment was her sophisticated process of navigating these questions of authority and truth.

When students learn about Teresa they can discover how people possess more complicated relationships to religious truth and authority than the simplistic ideas that are often the default assumptions in public discourse. Once you've shown people that there's a way that they can perceive new things about their own experiences because of a literary source, something else becomes possible. But you can't just do that with one talk or one public event. There has to be some sort of relational context for that to really happen. That’s why classrooms matter, why teaching matters, why being in person, in real time, is so important. It’s not about “religious literacy” or a list of facts that anyone can read on Wikipedia or ask AI to tell them. It’s about what can happen in the spaces where people are reading and thinking and talking together.