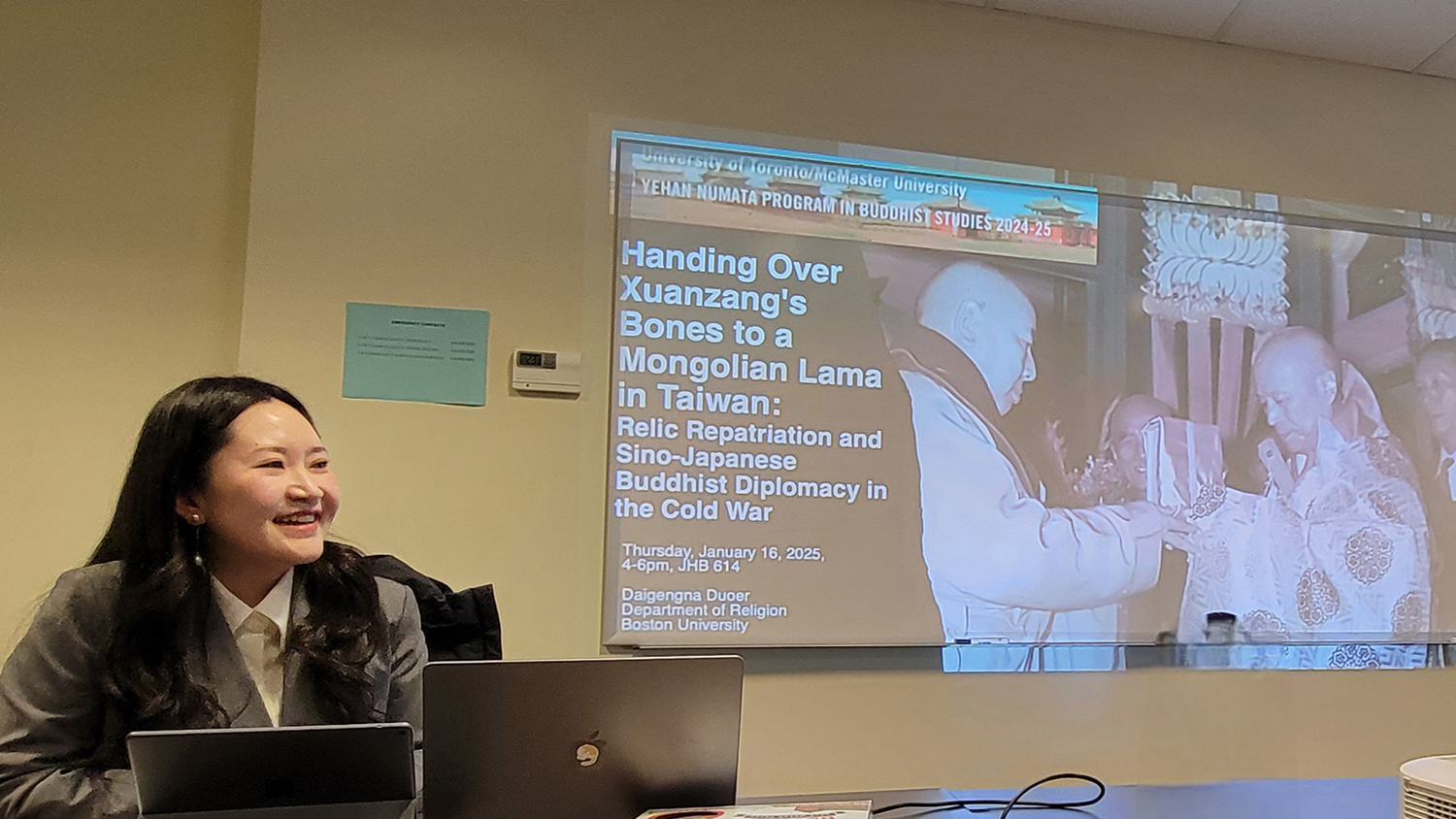

In January 2025, Prof. Daigengna Duoer was our DSR Lecture Series guest speaker, returning as a Buddhist Studies alumna of the Department for the Study of Religion (BA, 2012; MA, 2017). She presented “Handing Over Xuanzang’s Bones to a Mongolian Lama in Taiwan” to a full house, a lecture co-presented with the Yehan Numata Program in Buddhist Studies.

An assistant professor in the Department of Religion at Boston University (PhD Religious Studies, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2024), Duoer specializes in modern East and Inner Asia, focusing on 20th-century transnational Tibeto-Mongolian Buddhism. Her first book (forthcoming) is entitled Buddhism Beyond the Nation and the Empire: Transnational Buddhists in Modern East and Inner Asia. In it, she examines Buddhism’s roles in the context of the competing nation and empire-building projects that took place in early 20th-century Inner Mongolia and Manchuria – regions sandwiched between the expansionist ambitions of Republican China, the Japanese Empire, and the Soviet Union.

Duoer met with DSR PhD candidate Ian Turner to talk about her path through the study of Buddhism, history, politics and the rewards of sparking curiosity in students. The interview has been shortened and edited for clarity.

In 2016, as an MA student in Buddhist Studies at the DSR, you published a news article on a Yehan Numata Program guest speaker. How does it feel now to be back at U of T, on the other side of the table?

It's surreal. A friend from those years said to me, "this is such a full circle moment for you". That's exactly it! The biggest takeaway from those guest lectures was: "oh, so this is how you can actually approach the study of religion and Buddhism specifically!" At the time, I was just an MA student, I had no idea about what methodology really was, let alone my own methodology! I had no idea about what I really wanted to research. I would go to those talks, and started to think, "what kinds of questions do I want to ask? What do I really care about?" So, it's exciting to be on the other side. It's one way to give back to the department that gave me the foundation of my education.

Let's talk about philology and language training, which I imagine sets you apart as a 20th century historian. In addition to the Buddhist Studies skillset, was it also one demanded by your field of Inner and East Asia, and your interest in transnationalism?

Definitely. Classical languages, Tibetan, Chinese, I studied to do philological work. But modern languages, Chinese, Japanese, Mongolian, Korean, Russian, I really needed them, because of the sources, right? The questions I had been asking demanded those language skills. Scholars point you in a certain direction. Or, you know this archive has materials that will help answer your question. But then they're in Mongolian, or in Cyrillic script, or in Russian. There's a wealth of material on Buddhism in the early 20th century in my region, Southeast Mongolia, all in Japanese. As a foreign national, it's very difficult to access archives in the PRC. Luckily, Japan preserved all its pre- and inter-war materials, which really is a wealth. It's a good problem to have, but it’s kind of lonely in this field of Inter-Asian religion because you can do a lot of new work without many sources to cite.

Is the transnational part of that isolation? What work does that orientation do for you and where does religion play into it?

It came naturally, again because my questions, the material and stories, demand this perspective. For a while, the translational approach was really challenging because you're doing multiple sets of work, multiple perspectives, sometimes conflicting information. There's this old Japanese story where everyone is telling their version of a murder. As a detective, you must make a judgement over who's telling the story, but when you don't have concrete factual evidence, all you have is this hall of mirrors. That's what doing history feels like, it’s very scary. But you have to say something, along with the responsibility for that interpretation and the multiple narratives. The transnational approach helps.

But then the caveat is, “let me tell you what real Buddhism is. Obviously, your Buddhism is under-developed. You're not very civilized."

There are two ways that I understand this. One is because Buddhists and Buddhism travel across borders. It's one of those religions that is very, very global. Another is that even looking at just one region, like Inner Mongolia, it has this transnational layered history, with different empires and nation states competing to take it over. And you also have local groups, communities, politicians envisioning their own worldviews. Or ethno-national ideas. So, I think there's a very localized sense of the transnational, a kind of layer that is enforced on top of a group of people or a land. So, when you're staying put, you're also dealing with the transnational. I'm trying to incorporate both approaches in my book.

Then, you also have these very modern intellectuals, educated in Russia or Japan. Or even Europe. But you also have monks or lamas, right, who travel across borders. These are usually the so-called "important" ones, socially and politically influential. They were invited into this pan-Asian esoteric-Buddhist brotherhood. "We need to unite to fight – the communists, first of all. We also need to fight the Euro-American imperialists." But then the caveat is, “let me tell you what real Buddhism is. Obviously, your Buddhism is under-developed. You're not very civilized. Barbarous, even." And then, the ones who can't afford travel? They also have to deal with this issue of "where do I belong? What is the future of Buddhism?" They try to find a place for themselves, to describe what's happening around the world, through Buddhist lenses.

A component of your research and teaching concerns Digital Humanities and mapping. What does this methodology, and the trans-regional, trans-national, digital map of Buddhist networks you've developed, contribute to the fields of study we've been discussing?

I always appreciate when people ask me about this map. I feel like the dissertation is more of a homework assignment, the book I see as a service to my field. But the map is very personal, my baby. For the longest time, when you do any kind of research on Mongolia, or Inner Mongolia, you have this issue of place names. You have a Tibetan place name, or a Chinese place name, or sometimes a Mongolian name, but spelled in weird ways. I felt there needed to be a resource where you can easily look up these things [people, monasteries, colleges, etc.].

And mapping is a great teaching tool, too. With the software subscriptions that most students are paying for already, you can easily create a map. And I thought, well, this could be one of those transferable skills. These students are digital natives, the technology is not really an issue because it's so intuitive now. What we can provide as humanities educators is, first, what questions to ask. Students come in waiting to be fed with information, to be tested on something, to get a grade, and move on. But I think the value of us lies in sparking or nurturing curiosity, so they can start to ask questions that are meaningful to them – not necessarily to us, right, because we have our own questions. The class I first tried this on [mapping Buddhist communities of Southern California] took to it so well. Getting them to become curious about these people, these real people who are living in our backyards, going out there and talking to people that they probably never cared about before, was the hardest thing but also the most valuable thing. I think my teaching moment is really there, not in the digital space.